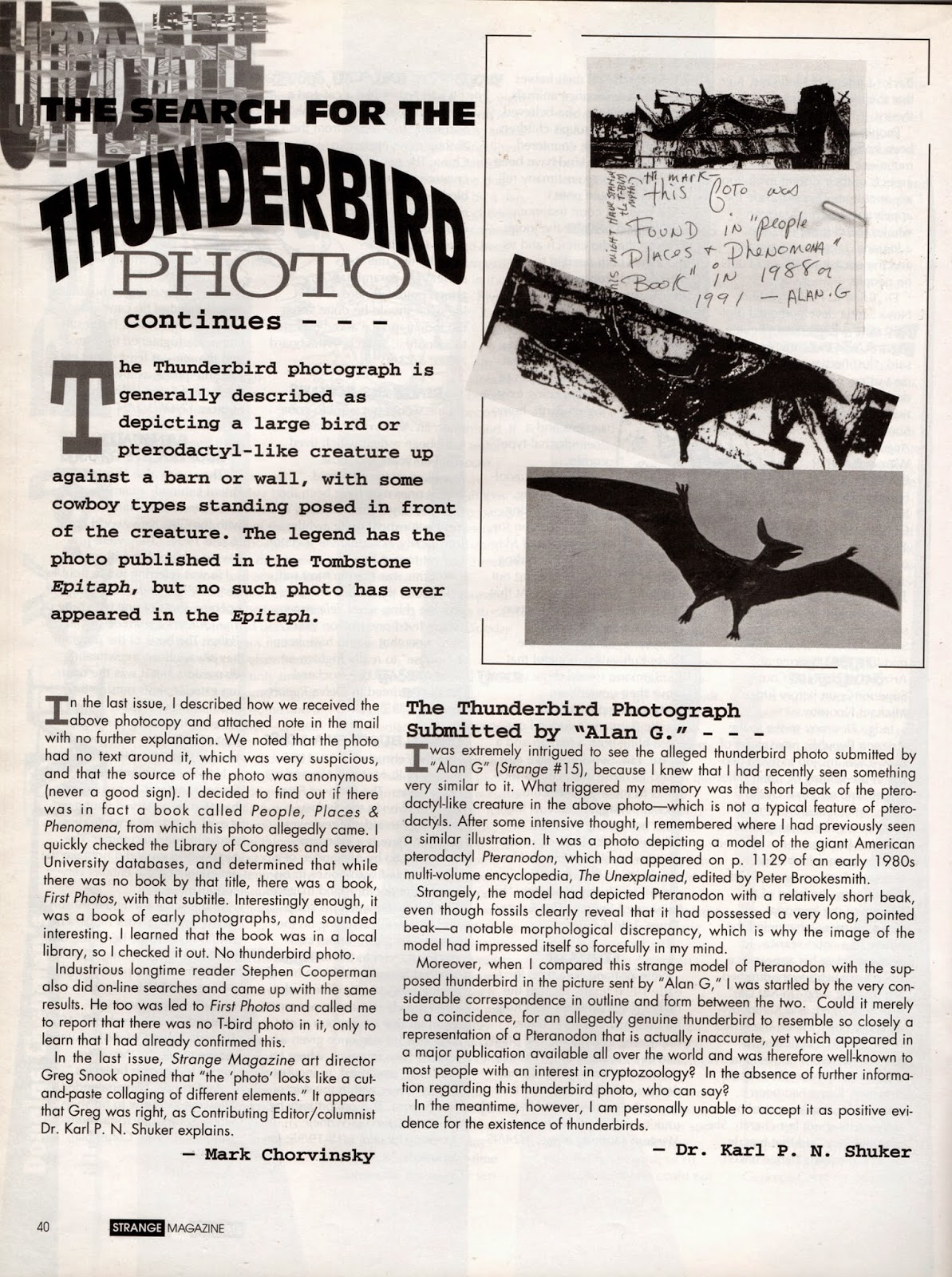

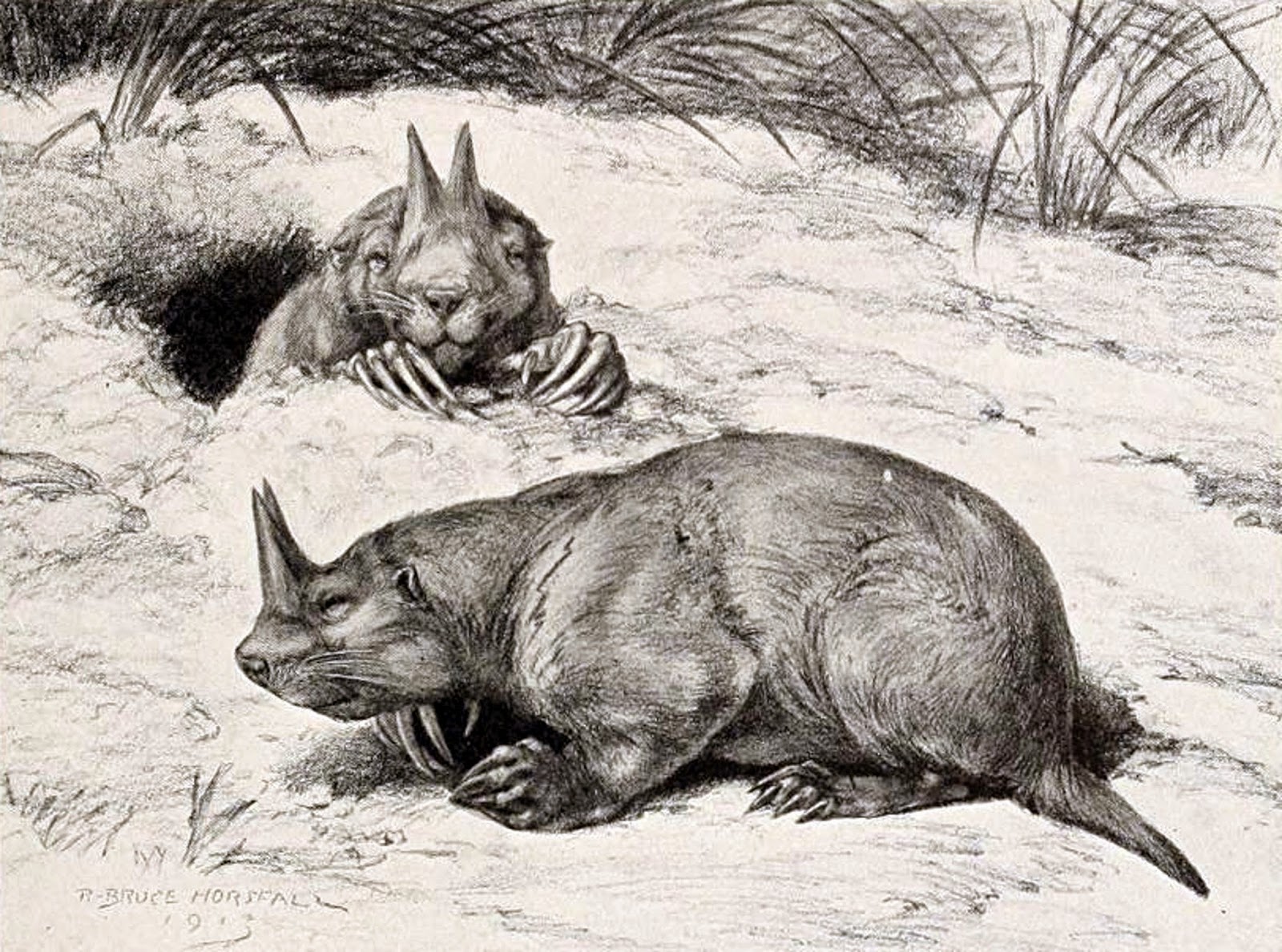

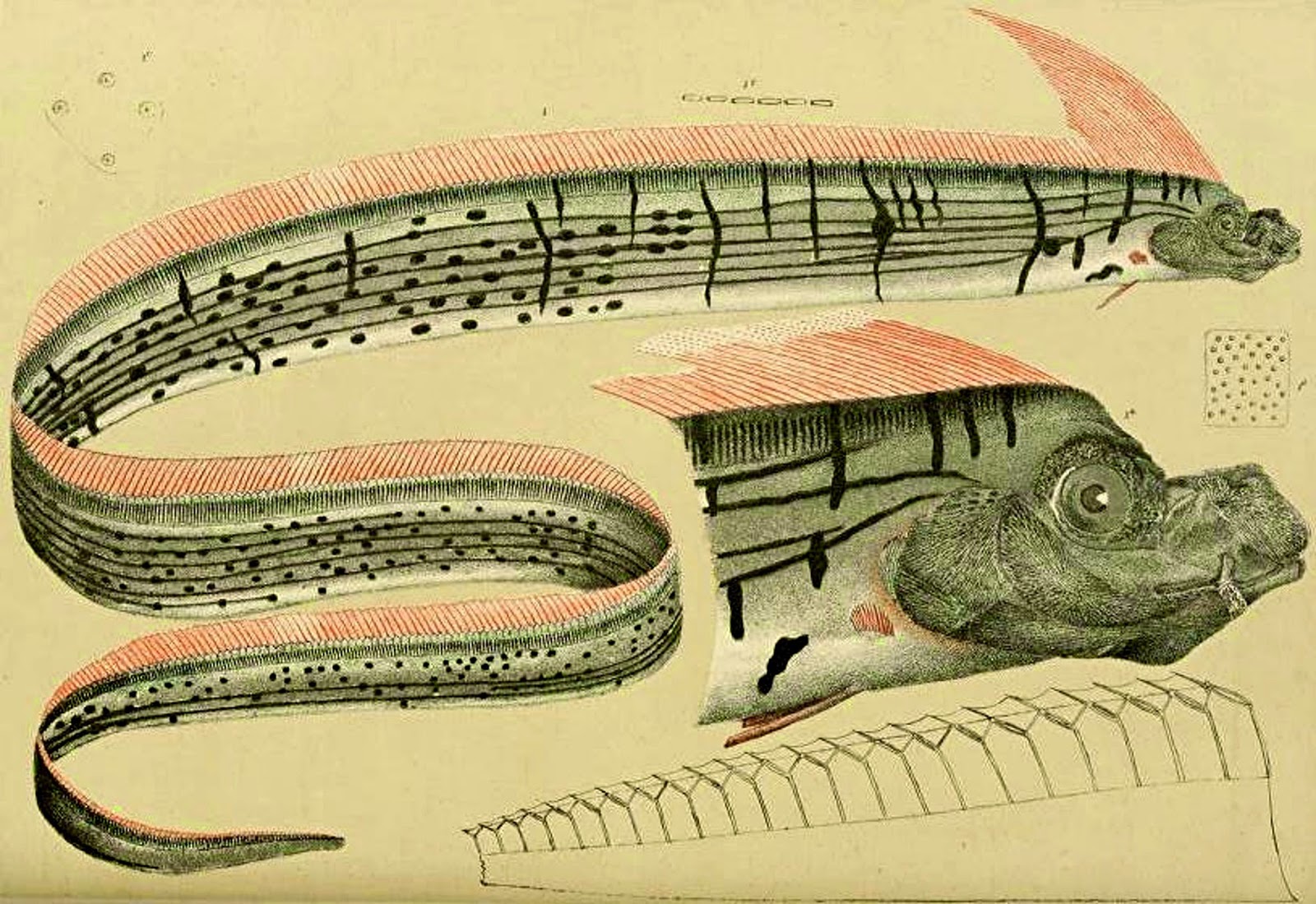

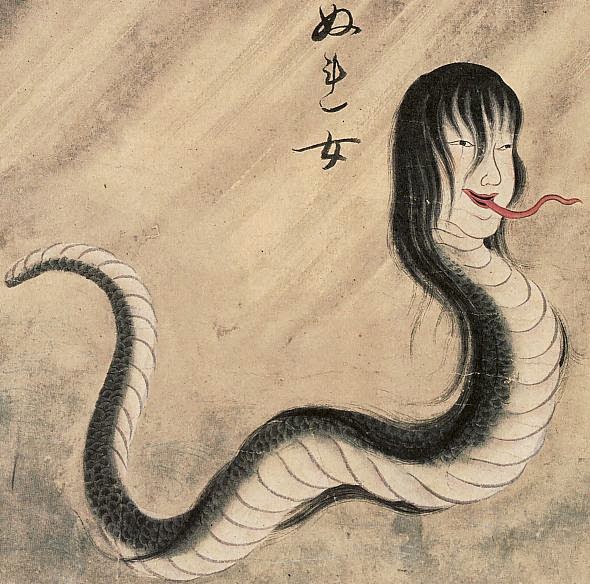

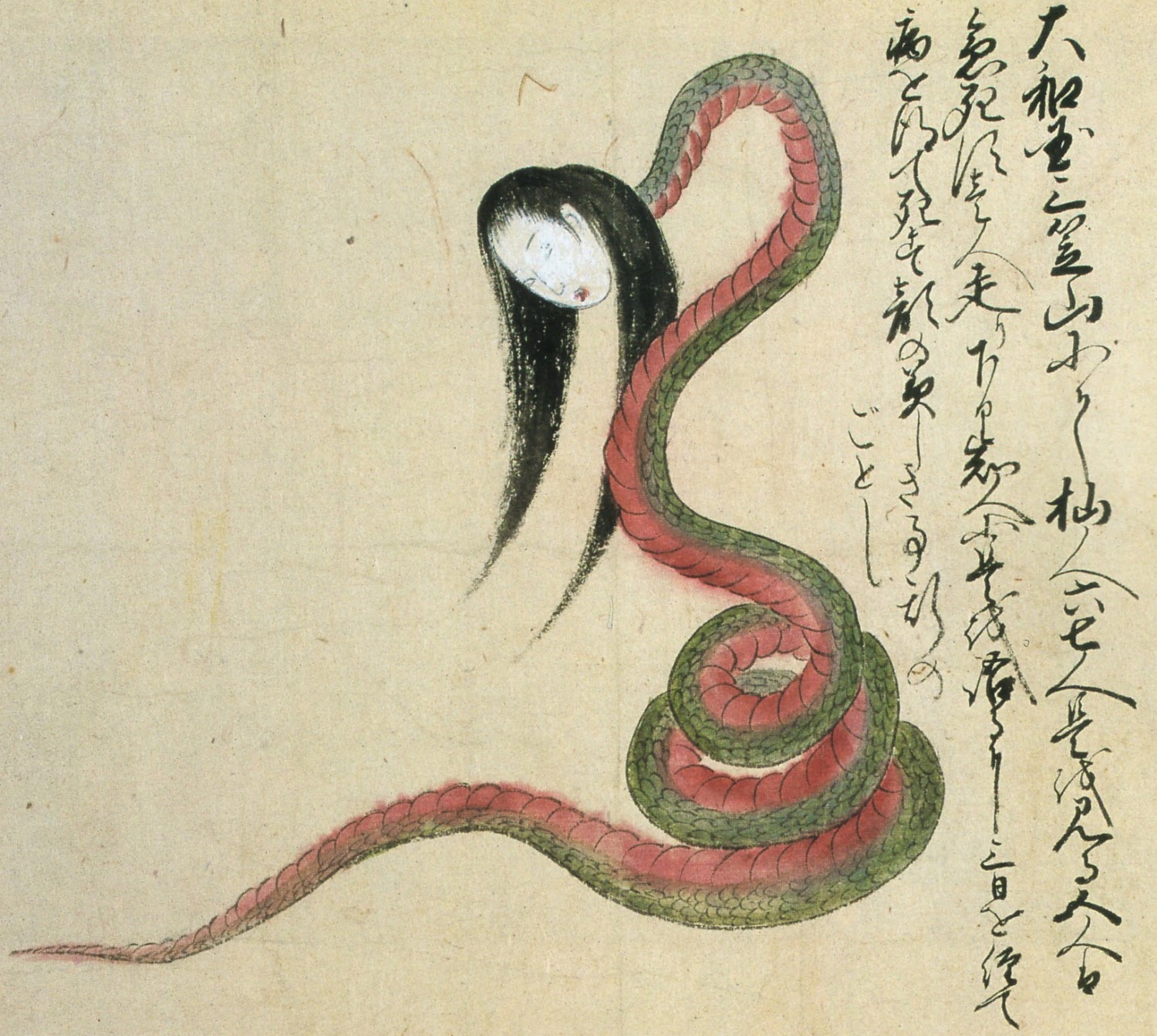

Nure-onna, by Sawaki Suushi, 1737

Imagine a land infested with rapacious shape-shifting spider-maidens, hideous blood-sucking hags with razor-sharp talons, gigantic fire-breathing roosters, green-skinned rubbery ghost-turtles, enormous disembodied skyborne heads foretelling thunderstorms, and innumerable other monstrosities of mayhem. For what is, geographically-speaking, a relatively small, insular nation, Japan has an extraordinarily diverse pantheon of traditional mythological monsters, many of which are known collectively as yokai. These exist in every form imaginable – and, in some cases, wholly unimaginable! – but are united in their frequently nightmarish appearance and ferocious behaviour.

Think of every conceivable way in which a human can be captured, torn apart, and bloodily devoured, and the chances are that there is a yokai designed specifically for that role. Clearly, ancient Japanese culture had an inordinately febrile collective imagination (either that or there was something very strange in the sake!), but rarely has this been more effectively demonstrated than in the folklore appertaining to two of the yokai clan’s most fiendish members – the nure-onna and the ushi-oni. And to make matters even worse, whereas even a single yokai is usually more than sufficiently horrifying for all but the bravest of persons to confront, the nure-onna and the ushi-oni often join forces to create a terrifying partnership designed specifically to ensnare and engulf anyone unfortunate enough to chance upon these foul entities.

Now, drawing upon traditional yokai lore, here is how I envisage such a fearful encounter may unfold. So, be warned – if you have a loathing for serpents, a horror of spiders, or, even worse, a terror of both, this is definitely not the place to be!

It was a warm summer’s afternoon when the young fisherman took his new bride for a walk along the coastline of Shimane Prefec-ture in western Japan. Having lived her entire life in the city, where they’d met and fallen instantly in love with one another during his very first visit there just a few months earlier, she had never before even seen the sea, and was delighting in the gentle roar of its distant waves, the raucous cries of the gulls overhead, and the soft caressing foam that lapped around her feet as she stepped over stones and seashells at the very edge of its fluid turquoise domain.

Her husband, walking behind her, smiled at her laughter and child-like enjoyment of this totally new experience, and even the clouds that had threatened earlier to overshadow their afternoon had drifted apart, welcoming the golden sunlight that flooded the scene and danced in dazzling glee upon the sea’s shimmering surface. It was an idyllic scene – too idyllic, perhaps.

Rounding a corner, the two walkers were startled to see what looked like a young naked woman, submerged from her waist down, leaning upon a rocky outcrop just ahead of them as she combed with great care and attention her long, luxuriant hair that flowed all about her, rippling in the cool sea breeze, and as black as ebony. Again and again she combed these dark locks, until they gleamed like rivulets of Night. And next to her, placed precariously upon one of the rocks, was a bundle, wrapped roughly in rags – but which looked suspiciously as if it may contain a baby.

Yet the young woman paid no attention to it whatsoever, devoting herself entirely to the obsessive combing of her sable tresses. The fisherman’s bride was fascinated by this incongruous scene, so much so that she failed to see the expression of absolute horror that had frozen her new husband’s face into a silent, rigid mask. Indeed, so transfixed was he by what he was seeing that he was unable even to scream out to his bride as she moved closer to the young woman.

Suddenly, the woman looked up, and saw the bride approaching. Concerned that the bundle, which she felt sure was indeed a baby, may topple off the rock and fall into the sea, the bride was walking towards it. As soon as she realised this, the woman picked up the bundle, held it close to her breasts for a moment, and then, gazing directly at the bride and smiling, offered it to her in outstretched arms.

Nure-onna, by Toriyama Sekien 1781

Finding his voice at last, the petrified young fisherman opened his mouth and let out a single desperate shriek of warning – but it was too late! His bride, smiling back at the strange woman with the long black hair, had stretched out her own arms and had taken the bundle in them, gently and welcomingly.

She bent her head down, to look at the face of the baby that she expected to see looking back out at her from the humble bundle of rags that she was cradling – but her frantic husband knew only too well what she would see, and it wouldn’t be a baby.

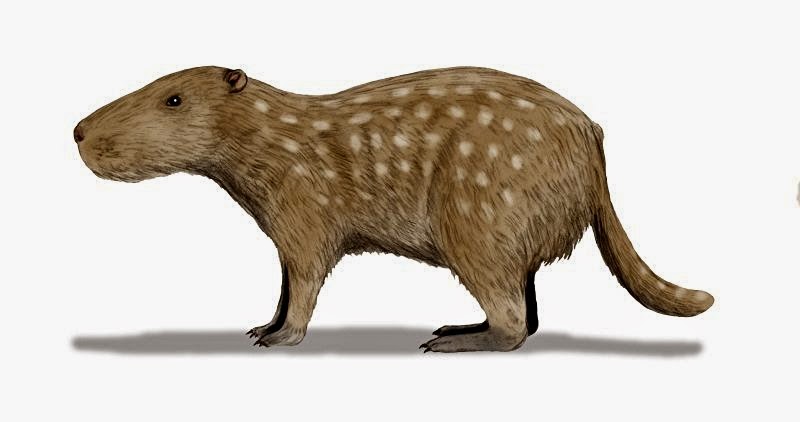

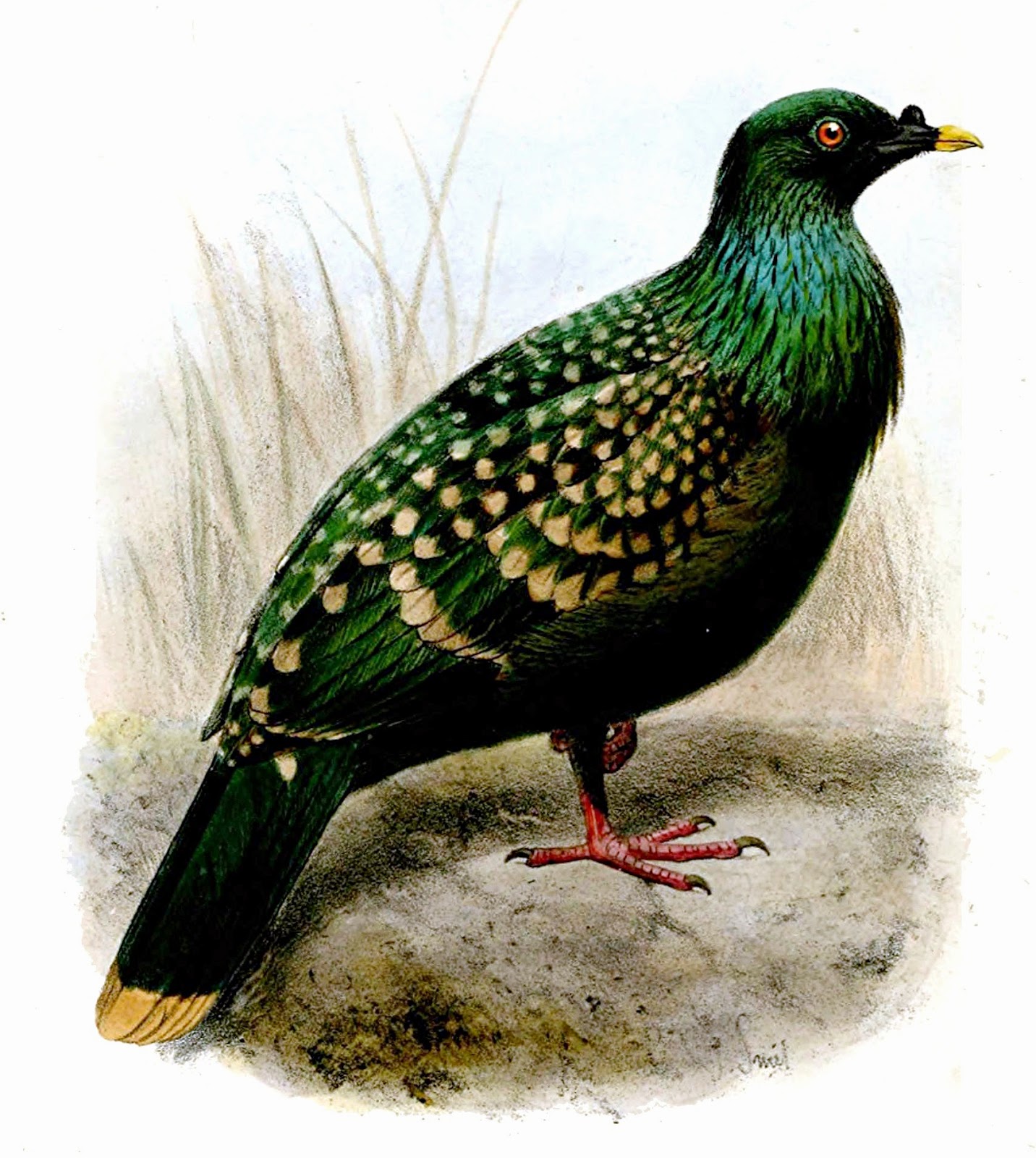

Raised in a small coastal fishing village nearby, he knew all about the horrors that lurked in the ocean depths and occasionally came ashore – the evil maritime yokai that sometimes assumed human form to tempt and terrorise the mortals who shared their coastal domain. Varied indeed were their forms, but few were more horrific, and deadly, than the nure-onna. As lethal as an iceberg, this malevolent entity further resembled one inasmuch as most of her immense form remained hidden beneath the surface of the sea, with only a small proportion appearing above it - which invariably assumed the innocent guise of a coy young woman combing her long inky-black hair, with a bundle of rags placed beside her.

And if anyone should be unfortunate enough to encounter her, and to approach her little bundle, the woman would offer it – but never, never, should it be accepted!

If only he could have put this wisdom to good use, but his unsuspecting bride had already taken the bundle in her arms, and even now, as he watched, he saw her head jerk back in shock at what she had seen concealed amid the rags.

There was no baby! True, the rags had been artfully arranged to give the impression that they contained an infant, but what they really contained was nothing more than a very large, heavy rock!

Startled, and totally perplexed, the bride looked at the young woman, and as she did the woman grinned back at her, a malign, vicious grin that exposed a formidable array of sharp teeth, including a pair of long curved fangs that dripped with amber venom. At the same time, the waves behind her began to froth and surge, as if something enormous had risen from their dark, sequestered depths and was about to break forth through their mirrored surface – which is precisely what was about to happen.

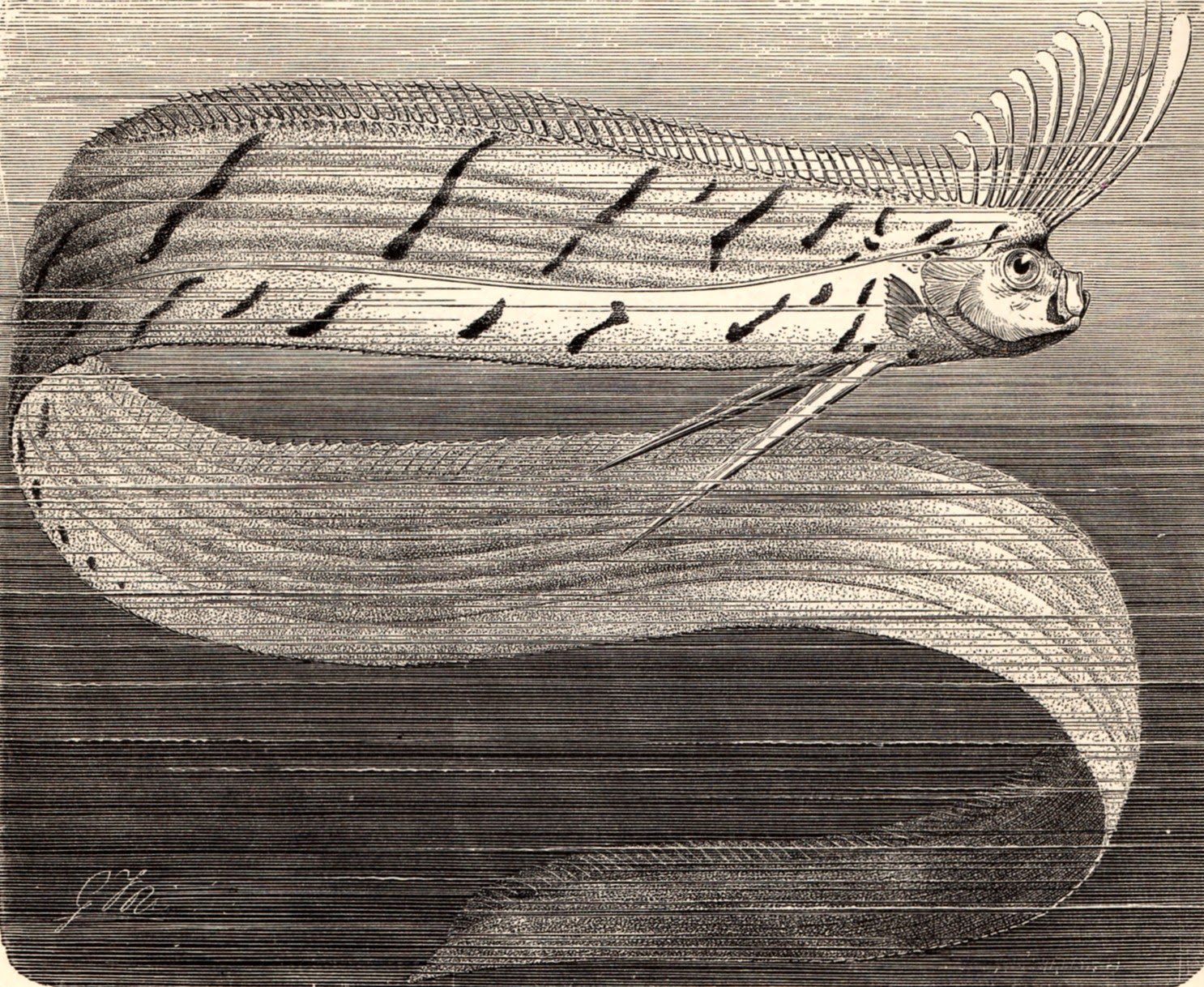

Suddenly, a series of enormous scaly coils, seemingly limitless in length, appeared, thrashing wildly as they sent great showers of spume and seawater cascading in all directions. And as the bride gazed at this blood-chilling scene, the young woman began to rise up in front of her, revealing that she was only semi-human. Below the waist she was entirely reptilian, or, to be more specific, serpentine - for the remainder of her form consisted of those vast ophidian coils, which in total measured at least 300 metres, stretching back as far as the eye could see as they undulated madly in a ceaseless frenzy above the whip-lashed sea surface.

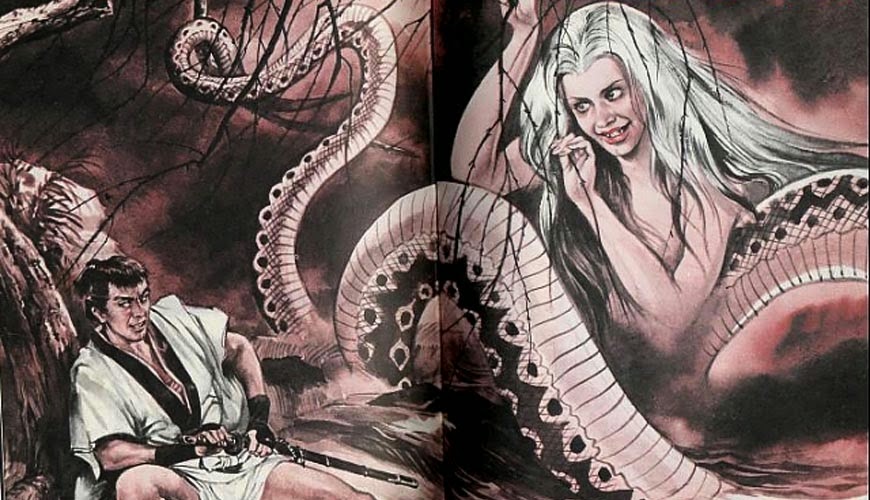

Nure-onna (© Gojin Ishihara, 1972)

There could be no doubt – just as the fisherman had feared, the marine demon confronting his doomed bride was none other than a nure-onna, the gargantuan, merciless snake-woman of the sea. Surely, then, there could be no escape for his beloved, or, indeed, for himself. For as if the scene facing them were not already horrifying enough, the fisherman knew that worse was still to come – because the nure-onna rarely appeared alone. Waiting to participate in its inevitable feast of human flesh was, assuredly, an equally voracious sea-monster – the ushi-oni.

As soon as his bride attempted to flee, by hurling the rag-enveloped rock away or even directly at the snake-woman, she would feel as heavy as the rock itself, rooted to the spot, unable to take even a single step away from the loathsome humanoid serpent rearing up before her. Then this monstrous creature would flick its huge tail forward and coil it around his helpless bride’s paralysed body, lifting her up to its open jaws, out of which its long scarlet tongue would emerge, wrap itself tightly about her in an unyielding vice-like grip, and proceed to drain every last drop of blood from her body until she was nothing more than a shrivelled, etiolated corpse.

But instead, something extraordinary happened. The fisherman’s bride had no knowledge of the sea, its traditions, and the countless monsters that it concealed, but she had not only the innate maternal empathy that all women possess but also the cool-headed, quick-witted confidence that a life spent in the bustling heart of a big city had readily bestowed upon her. Not easily frightened, and reared upon science and logic rather than folklore and superstition, she was well-equipped to deal rationally even with extreme situations far outside her normal limits of experience. Consequently, intuition and innovation now united in the briefest tremor of time to offer her a single chance of escape – if she was brave enough to take it.

The nure-onna’s huge tail had already lifted itself out of the raging waters of the sea and was surging shoreward – within just a few seconds it would be wrapping itself around its victim’s body. But even as it moved forward, so too did the bride’s arms, as, with all due care and reverence, bowing her head respectfully towards the colossal creature - and in spite of her great fear - she offered the wrapped rock back to it.

The nure-onna’s eyes, which only moments before had glowed in unholy, exultant joy, now betrayed visible flickers of surprise and even bewilderment as they glared down upon this slight human form giving back to it as a tribute in unspoken supplication its pseudo-child, still wrapped in its rags, and tenderly handled with evident sincerity.

Never before had this happened! In what seemed like the passing of a single heartbeat that yet spanned eternity, the nure-onna reflected on what course to take, as the bride remained with bowed head before its upraised form, and her husband stood a little way behind, as still and silent as a statue, frightened that even the faintest movement or murmur from him might break this extraordinary spell and bring instant death upon both of them.

And then, slowly, almost hesitantly, the nure-onna stretched out its arms, and took the bundle from those of the bride, and, as before, held it for a moment to its breasts. Its colossal tail, which was still upraised, and by now almost touching the bride - who remained standing with head bowed before this gigantic sea-demon - dropped back into the sea, sending a mighty wave crashing about the shallows, as it sank down beneath the surface. And as the tail sank, so too did the nure-onna’s huge body coils, vanishing one by one back down into the cavernous lightless unknown kingdom far below the sea’s upper levels.

Soon, nothing remained above the surface but the human portion of the nure-onna, who looked once more at the bride and also, momentarily, at her husband, before it too disappeared beneath the waves. Not a trace remained now of the gargantuan monster that only moments before had filled the shore and had stretched back out as far as the very horizon itself.

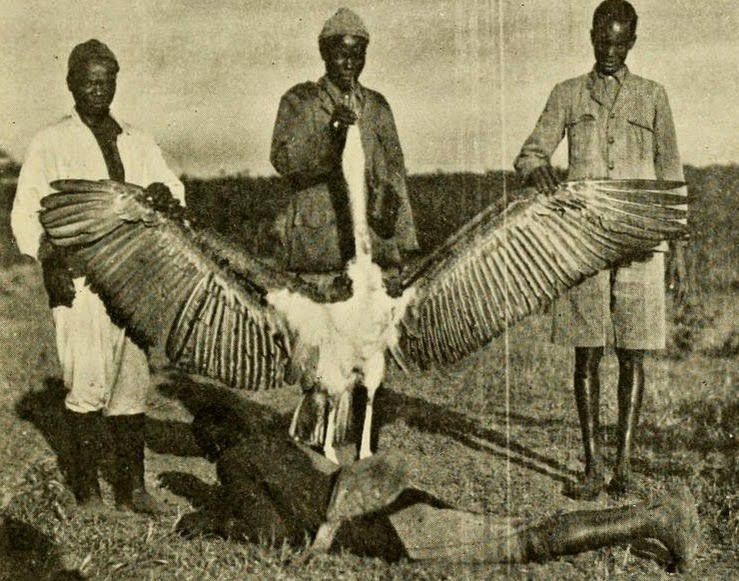

Snake-woman from Mt Mikasa, resembling the nure-onna, depicted in the Kaikidan Ekotoba (a mid-1800s hand-painted scroll profiling 33 Japanese monsters and human oddities)

As if released from a spell of petrification, the young bride began shaking with hitherto-suppressed fear, and her husband ran up to her, and held her within his arms. He wanted to tell her so much how it was all over now, that they were safe, and that everything would be fine – but he knew with dread certainty that it was far from all over, that they were anything but safe, and that the prospect of everything being fine was slim in the extreme.

And even as these dark thoughts soared through his mind on shadowy wings of panic, the sea before them began to surge again. The nure-onna? Surely it had not returned? The bride opened her mouth to scream, but at the same moment her husband dragged her ashore, and began to run back from its edge with her, pulling her with him as he raced across the pebbly beach, moving as far away from the shoreline as possible. But then came the noise that he had hoped never to hear – an ear-splitting bellow of rage that sounded like the loudest roar ever voiced by the biggest, most ferocious bull that ever lived. And in a sense, that is exactly what it was – except that the bull in question was no ordinary specimen.

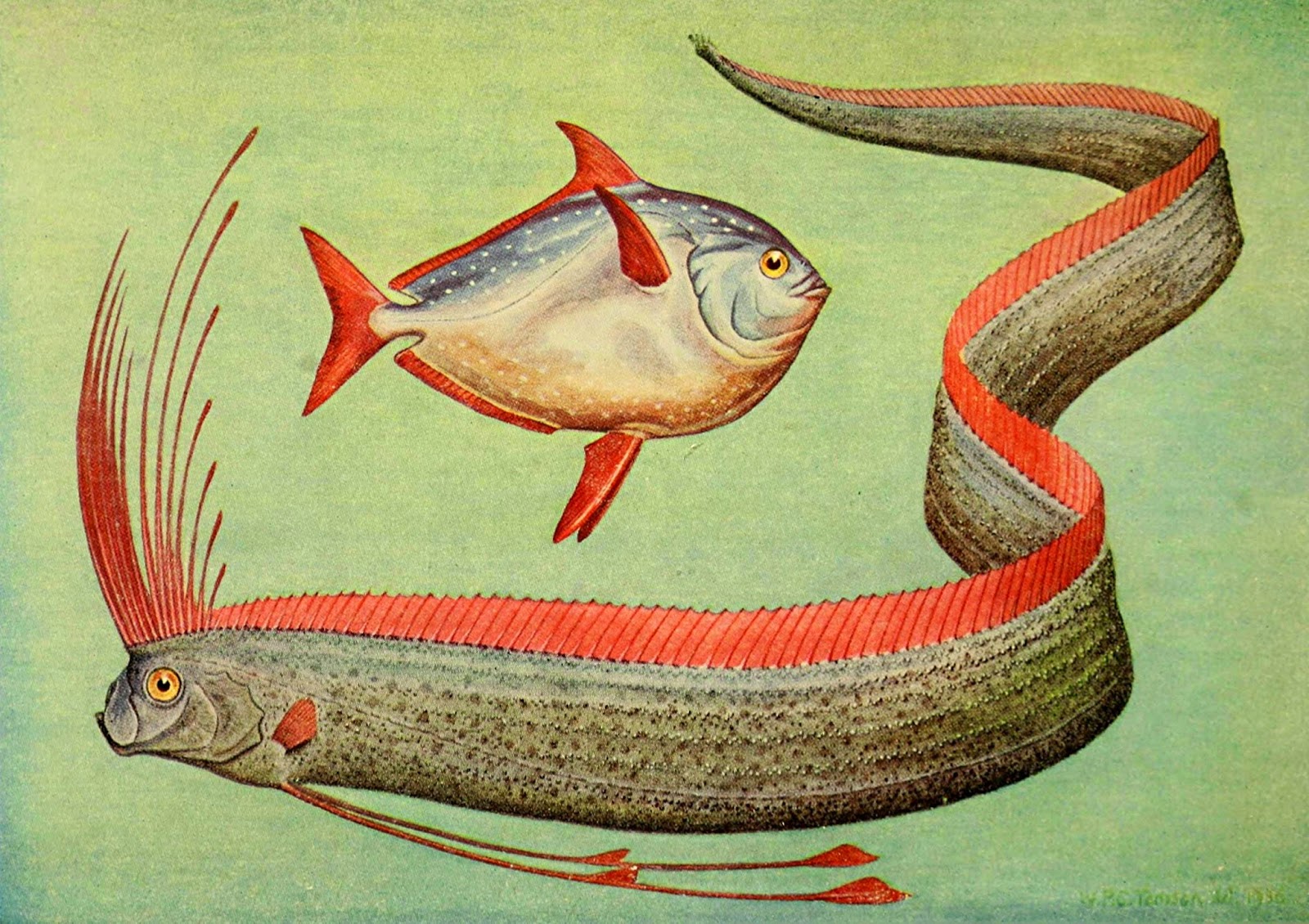

When they heard this terrifying noise, the two young people turned round to look back – and saw a creature so horrific that even the nure-onna suddenly seemed a little less frightening than it had previously done! Standing on the very edge of the shore, still wet from having just emerged from the sea, was a monstrous beast that the fisherman immediately recognised as an ushi-oni.

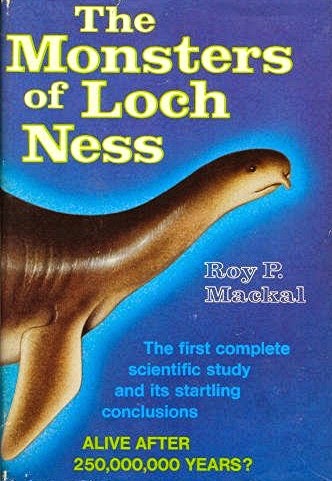

Its massive head was like that of a huge black bull, armed with a pair of mighty horns, but it also had flaming crimson eyes, flaring nostrils that spewed forth dark, caliginous clouds of fiery smoke, and open jaws that betrayed the presence of numerous sharp, unequivocally carnivorous teeth – far removed from the cud-chewing molars of normal cattle. Yet if its head seemed bizarre, the rest of this sea-spawned nightmare was positively surrealistic – for eschewing the typical four-limbed bovine form that might have been expected to complement its head, it instead sported the hideous eight-limbed body of a colossal spider!

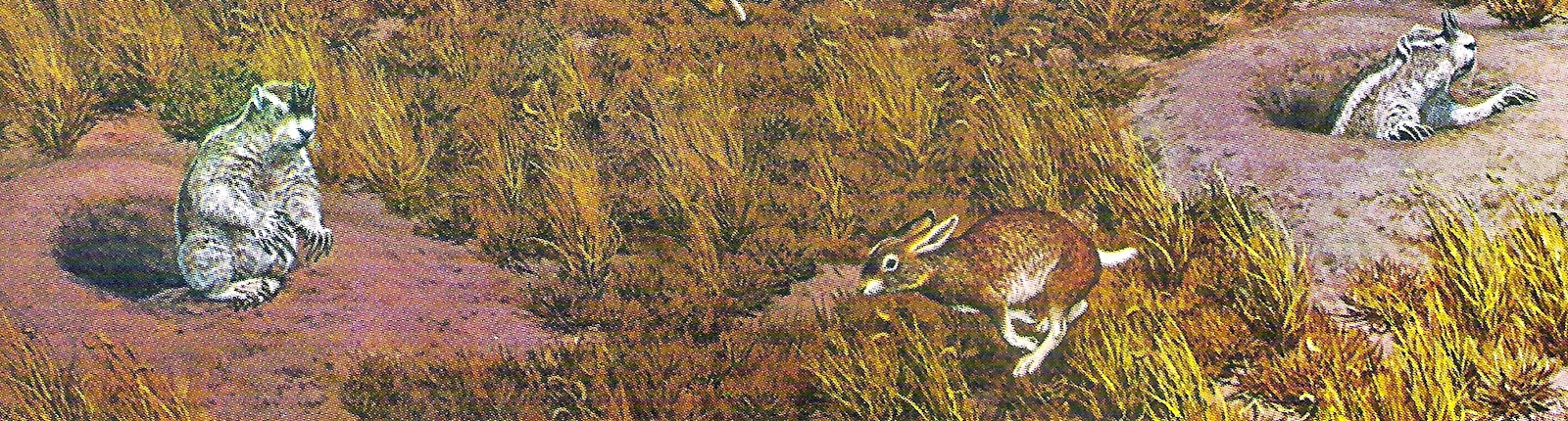

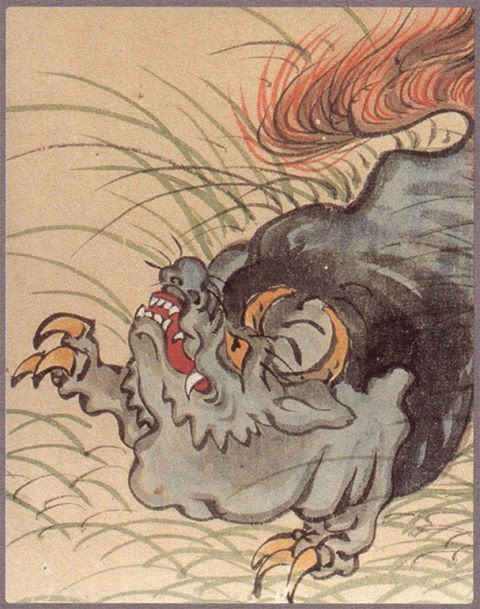

Ushi-oni, by Sawaki Suushi, 1737

Although the ushi-oni was paying close attention to the fisherman and his bride, it also seemed somewhat distracted, its head periodically swinging from side to side as if searching for something. The fisherman realised that it was looking for its fiendish collaborator, the nure-onna, puzzled that it was not here, ready to help seize these puny humans cowering on the beach.

Seeing the monster’s hesitation, the fisherman grabbed his bride’s hand and raced off along the way they had come earlier that afternoon, towards the cliff face and onward to the passage that led back through the steep rocks to their village. But their sudden flight alerted the ushi-oni, who scuttled after them in deadly pursuit, the absent nure-onna now forgotten as it threw back its head and roared again in bellicose fury.

Unaccustomed to running at speed across the uneven pebbles, slippery rocks, and treacherous stones half-hidden beneath the shifting sands, the fisherman’s bride slipped and fell several times, and each time that he stopped to pick her up, the ushi-oni gained ground. Desperate to elude it, the fisherman abruptly changed course, cutting back on his previous route in the hope that they could escape through some rocky crevice large enough for he and his bride to slip through but too small to permit the gargantuan ushi-oni to do the same.

But even as they ran on, his bride was tiring, physically weary from their prolonged flight and mentally exhausted from her earlier terrifying ordeal with the nure-onna. Very soon she would be unable to flee any further, the ushi-oni would catch up with them, and then...

Frantically seeking any possible escape route, the fisherman suddenly spotted a v-shaped high-walled passage opening up ahead between the rocks. Its widest point was its entrance, so if, once inside, they could run along its corridor and exit at its furthest, narrowest end, they would leave the ushi-oni far behind, because the passage’s exit, although hidden in shadow at this distance, would undoubtedly be too small and tight for the ushi-oni to force its way through. With relief buoying their flagging spirits, the two young people ran directly towards the passage, entering its shadowy, narrowing corridor just moments before the ushi-oni arrived behind them.

They ran down the corridor at full pace, towards its furthest end, looking for an opening amid the shadows that would grant them a secure escape from the bloodthirsty spider-bull. Then, a dark aggregation of clouds that had been eclipsing much of the late afternoon’s sunlight finally drew back, enabling the sun to send bright shafts of light down upon the cliff face and into the passage where the fisherman and his bride were anxiously seeking the exit.

Ushi-oni (© Anthony Wallis)

And as it did so, they looked at each other in horror. With the shadows obliterated, they could see only too clearly that there was no exit there after all – the passage was an unbreachable cul-de-sac of solid rock, whose sheer, steep-sided walls offered no means of escape either. They were trapped! And bearing down upon them was the ushi-oni, blocking the entrance and glaring balefully at its imprisoned prey as it attempted to squeeze its repulsive arachnid body ever closer towards them down the narrowing passage.

Faced with certain, horrific death, the shattered mind of the fisherman’s bride abruptly shut down, and she collapsed unconscious at his feet. But even as he knelt to gather up her prone form, he too knew that it was surely over. The monster was now so near, clawing its way as it strove to force its bloated form down those last few metres separating its salivating jaws from its victims, that the fisherman could feel its sulphurous breath burning his face and taste its acrid fumes choking his throat.

And then he remembered his grandfather and their family’s sword. Like so many others living near the coast, the fisherman’s family was poor, but they owned a few precious, closely-guarded heirlooms, passed down through countless generations. One of these was a beautiful sword, whose hilt was ornately decorated with swirling symbols, and whose gleaming blade was razor-sharp and shone with a bright silver sheen even at night. As a small child, the fisherman had been earnestly informed by his grandfather that this was a magical sword, one that would come to the aid of any family member in dire need of its help. Needless to say, just like any curious child would have done, the fisherman had tried his best to entice the sword to come to him, but it had remained resolutely still. His grandfather had explained that it would only come if the need was urgent enough, but as he grew older the fisherman had suspected that this legend owed more to his grandfather’s renowned story-telling prowess than to any genuine magical ability of the sword.

If only it really had been true! Now, surely, more than at any other time in his life, the fisherman’s need for assistance from his family’s enchanted sword was sufficiently urgent. He pictured its intricate hilt, its flashing, sparkling blade, and his mind cried out to it, beseeching it to save him and his bride from the foul monstrosity whose black maw was already open wide, as it struggled unceasingly to haul itself close enough to engulf them.

It was no use. The fisherman held his still-unconscious bride up against himself, hoping to shield her for as long as possible from the ushi-oni’s voracious jaws. He closed his eyes, and prayed that their death would be swift. Then, without warning, he heard an extraordinary sound – a whining hum that was almost like a wordless song, and which, as it grew ever louder, seemed to be cutting directly through the air towards them.

The fisherman opened his eyes in wonder, and just as he did so, he heard what sounded like a single enormous clap of thunder. At that same instant, he saw the ushi-oni open its jaws even further and let forth a truly ear-splitting, bloodcurdling scream that chilled the fisherman to the bone and resounded inside his head until he was almost deafened by its booming echoes. Then, as he watched in mesmerised terror, he saw the fiery eyes of the ushi-oni grow dim, and close, and he watched its octet of scuttling spider legs shiver and buckle, until they could no longer bear the weight of the monster’s enormous body, collapsing beneath it as it dropped to the ground. It gave out one final groan, and a couple of its trapped limbs twitched a few times - then, silence, and stillness. The ushi-oni’s lifeless head swung down, crashing against the rocky ground. It was dead – their would-be destroyer had, instead, been vanquished itself – but by whom, or what?

Ushi-oni, by Toriyama Sekien, 1781

Once he was absolutely certain that the great monster was indeed no more, the fisherman rested his bride’s body gently on the ground, then, gingerly, he stepped around the edge of the fallen ushi-oni’s immense form. And there, buried right up to its richly-ornamented hilt within the creature’s swollen abdomen, was his family’s heirloom sword – the magical sword of his childhood whose power he had, as an adult, scoffed and discounted as a fairy tale – but not any more. Just as his grandfather had always claimed, if the need was sufficiently urgent, it would indeed come to the aid of any family member.

The fisherman leaned closer, grasped the sword’s hilt, and pulled back with all his might, and as he did so, the sword released itself from the ushi-oni’s body, and re-emerged, covered with foul-smelling black blood. Although he was trembling not only with cold but also with fear from all that he and his bride had experienced that day, the fisherman didn’t hesitate to take off his cotton tunic and wipe clean the sword’s blade, until it shone once more in the setting sun of early evening.

Then he walked back to his bride, and as he approached her he could see that she was stirring. He ran to her, placed the sword down, scooped her up in his arms, and kissed her mouth lovingly, feeling his heart leap as she opened her eyes, looked into his face, and smiled.

When she saw the dead ushi-oni lying before them, she jerked back and seemed about to faint again, but her husband comforted her, explained what had happened, and showed her his family’s marvellous sword. She looked at it in wonder, scarcely believing what he had told her, but after he had helped her to her feet, and pointed out the mortal wound that the sword had inflicted upon their seemingly invincible enemy, then she believed, and, like him, gave thanks for the protection afforded them by the sword. Afterwards, holding his bride’s hand in one of his own, and the sword in the other, the fisherman led the way back along the passage’s corridor, now entirely veiled in deep shadows, finally arriving at its wide entrance again, from where they stepped back out onto the beach. From here it was just a fairly short walk to the crevices that did lead through the steep rocks to their village on the other side.

Somehow, inexplicably, they had survived not one but two of the most formidable yokai that anyone could ever encounter, and had been rescued by none other than a magical sword. Their exploits would be celebrated for all time in the fishing community here, and perhaps it would never again be plagued by visitations from the nure-onna or from other ushi-oni. Then again, the yokai should never be underestimated. Even if these had gone, there were countless others ready to take their place.

Moreover, strange monsters are still reported occasionally from the wilder seas and shorelines around Japan today. Could they be unknown or unrecognised zoological species - or is this nation’s preternatural yokai clan very much alive and well even in our prosaic, ultra-scientific 21st Century? Ushi-oni (Oda Yoshi, 1832)

.jpg)